Insufficient Internal Education System:

Many companies are not dedicating sufficient resources to English education.

In essence, they rely solely on the personal efforts of their employees.

The extent of their effort often stops at encouraging employees to take the TOEIC exam, a trend in society to “not fall behind the global wave.”

The majority of managers, focused on cost-cutting to increase profits, do not see the feasibility of investing in English conversation classes or other company-sponsored language programs.

Workplace Atmosphere:

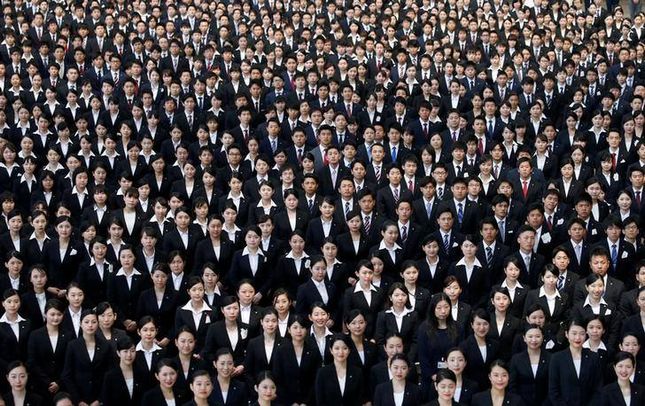

Japanese people excel at reading the atmosphere in a given situation, and it has become a habit ingrained in their nature.

This tendency is particularly strong among the younger generation.

While everyone struggles with English, standing out by studying and becoming proficient in it can lead to alienation in the workplace.

There is a fear of being labeled as an eccentric or curiosity-seeker, and in many companies that still embody a pre-war Showa era mentality, being a unique individual could mean professional isolation.

In an environment where conformity is highly valued, actively studying and using English is not likely to be embraced.

The prevailing mindset often leans towards fitting into the established norms rather than standing out, reflecting the Japanese cultural value of not sticking out like a sore thumb.

Cultural Differences in Business:

Learning a foreign language also means learning about the culture, customs, and values of that foreign country.

Virtues considered admirable in Japan, such as “reading the air” (kuuki o yomu), “non-verbal communication synchronization” (aun no kokyu), and “sensitivity to others’ feelings” (sontaku), may not be universally applicable.

Japan’s business culture has many distinct aspects compared to other countries, and when communicating in English, one must adapt to the business culture of the foreign context.

For individuals deeply immersed in Japanese society since birth, adopting and practicing different behavioral styles may be reluctant.

For those who are overly concerned about the opinions of superiors and colleagues, deviating from the norm is often considered unthinkable.

The prospect of embracing behaviors that stand out from the established social norms can be daunting for those who have been deeply ingrained in Japanese societal conventions from the beginning.

Lack of Motivation:

When there is a lack of motivation to learn English, staff members may not actively strive for skill improvement.

Except for the special case where English is a hobby, motivation often arises from incentives.

In other words, there needs to be a tangible reward or benefit gained from learning English.

Concrete incentives, such as faster promotions or raises for those proficient in English, are crucial compared to individuals who are not proficient in the language.

Without clear benefits, people are unlikely to invest their holidays or spare time in learning English.

True incentives and motivation for English learning arise when there are generous rewards that evoke envy and jealousy.

However, in reality, even with efforts to enhance English proficiency, internal evaluations may not improve.

It’s typical to see individuals with slightly higher TOEIC scores being burdened with translation or interpretation tasks, resulting in failure and a subsequent decline.

In such a situation, no one would be inclined to engage in English learning.

Considerations such as additional allowances proportional to TOEIC scores and providing separate training opportunities for translation or interpretation roles are essential to address this issue.

Workplaces Without a Need for English:

Surprisingly, there are many workplaces where English is not required for day-to-day operations.

This often includes businesses that operate solely within Japan, catering exclusively to Japanese clients.

Even in global companies, it’s not uncommon for only specific departments within the organization to engage in interactions with foreign people.

If a trading company is handling transactions on behalf of a department, there might not be a need for that specific department to use English.

In Japan, regardless of where you go domestically, Japanese is universally understood.

The dominance of a single language to this extent is a rare phenomenon on a global scale.

The linguistic uniformity and social insularity in Japan are noteworthy characteristics.

As long as one leads a typical life in Japan, there may be little perceived need to learn English.

Conclusion:

I have described the reasons why English proficiency does not improve in Japanese corporate workplaces.

There may be several factors in your current workplace that also apply.

Enhancing the English proficiency of staff members requires a comprehensive approach.

Let’s consider various perspectives and carefully identify the root causes.

I hope this article contributes to improving the competitiveness of companies through the use of English.